A strong and convinicing case can be put forward that On Her Majesty's Secret Service is the best James Bond film ever made. Admittedly handicapped to some extent by the absence of Sean Connery as Bond, whose

participation would have guaranteed the film's appreciation by a wider audience than is the case now, it is too often relegated to being a footnote in the Bond film saga when it truly one of its glories. As the latest James Bond film finally goes into production, Philip Masheter talks to star George Lazenby, director Peter Hunt, cinematographer Michael Reed, production designer Syd Cain and stuntmen George Leech and Alf Joint anout the making of OHMSS and some of the myths surrounding it...

Bored with the role that had made him an international star, Sean Connery had already decided that You Only Live Twice would be his last appearance as James Bond, and his experiences at the hands of the Japanese press were ample proof to him that it was time to get out. Wherever he went, photographers went too, and that included the bathroom.

Sitting in his hotel suite in Japan in the summer of 1966, Cubby Broccoli prepared the world for a Bond without Connery as the BBC's Alan Whicker probed him on this sensitive area. Still hoping that Connery may just be bluffing and would ultimately decide to return, he put on a confident front.

"It won't be the last one under any circumstances, with all due respect for Sean, who I think has been certainly the best one to play this part. We will in our own way try to continue the Bond series for United Artists because it's important, and if Sean doesn't want to do it, after all, we can't force him to do it. If he doesn't agree with our arrangements, or whatever it is, I can't say that he's wrong or right. And that's the end."

When asked about the inevitable headache in breaking in a new Bond, Broccoli continued on his philosophical tack:

"Everything is a headache in making a picture but you have to be determined to find a way to do this. And if Sean doesn't want to do it, and he has a right not to do it, this won't stop us from making another Bond because an audience out there want to see it. We'll present what we have for their approval."

The new film's greatest asset was its director, Peter Hunt, a Bond veteran of the highest calibre who was responsible for editing all the previous Bond films and second-unit work both credited and uncredited on a number of them. On Her Majesty's Secret Service was Hunt's debut as principal director of a Bond film, despite attempts to get the job on the previous outing, You Only Live Twice.

By the time of OHMSS Peter Hunt stood for all that was good in the previous Bonds and with the departure of director Terence Young following Thunderball, he was the remaining man most fully aware of what made the Bond series so distinctive and special. When Pauline Kael reviewed the lacklustre Diamonds Are Forever in The New Yorker, she wrote of Connery's return to Bondage after Lazenby's sole appearance in the role 'the only thing missing is Peter Hunt. ' That omission is something that has been felt and lamented ever since, because, even 25 years after it was first released and ten films later, OHMSS is the last great James Bond film.

It is salutory to note that even as early as OHMSS, Hunt was trying to halt the movement towards overblown, outlandish gadgetry which was already beginning to dwarf the character of Bond in both Thunderball and, to an even greater extent, You Only Live Twice. Enjoyable as both films were, the seeds of the series own corruption were evident and Hunt's answer to this was to return Bond to his resourceful best in a believable setting where vigorous physical action replaces giant volcanoes and space rockets.His task was made easier by his good fortune to have one of Fleming's very best novels as a starting point. The close similarity between book and film shows this determination to return to the closer adherence to Fleming which had made Dr No, From Russia With Love and Goldfinger so memorable. OHMSS was certainly the last Bond film that had any solid connection with Fleming, as Peter Hunt explains.

"It's the last one that we made in that series with the concerted idea of following Fleming's books from one to the other to the other. The only thing that happened was that You Only Live Twice should have been made after On Her Majesty's Secret Service by the chronology of the books. But they found themselves in this position of having a director on their books and they had had to pay him. And that was why Lewis Gilbert got You Only Live Twice. They did You Only Live Twice and I said, 'Fine. I'm going to still stay with On Her Majesty's Secret Service.' I always knew that that was a very good story.

"With Connery adamant that he would not be returning as James Bond, the search was on in earnest to find a suitable replacement. Convincing the press, while trying to convince themselves, that the Bond character was bigger than any single actor's interpretation of it, Saltzman and Broccoli began their search to find their new look Bond.

As director, Peter Hunt was obviously a key figure in this quest, the significance of which was keenly felt at all levels.

"We had a big meeting. When you come down to deciding a new James Bond it wasn't, at that time, just up to the producers or myself You had United Artists involved and they had to agree to it all. By the time you had finished you had to get agreement from Cubby, agreement from Harry, I had to agree and United Artists and all their hierarchy there: Arthur Krim and David Picker. So it was not an easy job and we had a meeting.

"I said, 'Now, when we're going to change this Bond, do we want to come modern and have a long haired one?' - because all that was in, or coming in. 'Do you want to have a young boy or a youngish man? Do we want to change the image and start with something to go on with?'"And there was a lot of discussion about all that and who of that ilk could fill the role. And in the end they said, 'No. Letís look for another Sean Connery type. ' And that was their concerted decision and I said, 'Fine. Okay, I agree with that because at least now we've got some idea of what we're looking for.'

"And that was what we started out with: testing the people who had that sort of sexual quality that Sean had."

Auditions began in early 1968 with the main emphasis on finding an unknown who would have no associations with any other role, as Peter Hunt continues.

"I tested a great many people for it. We were left with whoever was there at the time and I tested about fifty to a hundred people in various ways.

"By April there was a shortlist of five possible contenders. "I tested wonderful young actors like John Richardson. He was a handsome boy but didn't have that quality.

"The other four names consisted of three unknown English actors, Anthony Rogers, Robert Campbell and Hans De Vries, and a 29 year old Australian model, George Lazenby.

Dyson Lovell was working on the casting of the film, as he had on previous films in the series, and he had put together a list of male models that should be considered. At that time most of the successful male models working in Britain were Australian and were with Scotty's Agency in, of all addresses, New Bond Street, as was Lazenby. His recent television exposure as the crate-carrying 'Big Fry Man' in a well remembered commercial guaranteed that he would have been looked at for the part, as was Gary Myers, the 'Milk Tray Man' who blatantly borrowed the Bond image as he delivered his box of chocolates against impossible odds.

George Lazenby had become one of Britain's most successful male models, earning around £500 a week by the time of the Bond auditions. He had come to England in 1964 after a couple of years as a car salesman in Australia and began his modelling career at age 25 after fashion photographer Chard Jenkins convinced him that he could do well in the profession.

George Lazenby had become one of Britain's most successful male models, earning around £500 a week by the time of the Bond auditions. He had come to England in 1964 after a couple of years as a car salesman in Australia and began his modelling career at age 25 after fashion photographer Chard Jenkins convinced him that he could do well in the profession.

Since Lazenby would have been an inevitable candidate for at least some level of consideration, there is some confusion as to who actually found him, although initially his agent would have been the first likely person to put his name forward. This confusion has only been added to by the well-known story of Lazenby and his haircut in which Lazenby is supposed to have introduced himself to Cubby Broccoli, who spotted him at a barber shop. Lazenby explains,

"Well that was untrue. That came about because I went to the barber to get my hair cut like Sean Connery and Cubby Broccoli happened to be in there at the time. The barber pointed out to him later on: 'Remember that guy who got the James Bond thing? He was in here at the same time you were.' And he put that Cubby said, 'That guy would make a good James Bond, but he is probably a very successful businessman and wouldn't be interested ' And how wrong he was! I was in there getting my hair cut to go down to my first interview with him. I just wanted to get a haircut like Connery's and I knew where Connery got his hair cut.

"Extensive tests began in April with the five potential Bonds, much of it centring on how well they each performed physically in the fight scenes. George Leech, who had previously worked as an assistant to stunt and fight arranger Bob Simmons was in control on this film as Simmons had gone off to Spain to work with Sean Connery on Shalako. Leech and the film's director of photography, Michael Reed, both met on Broccoli's Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, for which he did the second unit work just prior to OHMSS.

A set was constructed to film the fight in the Portuguese hotel room between Bond and Tracy's bodyguard, with Yuri Borienko filling in for the performer who would actually perform the fight in the film. Borienko was a Russian who began working as a stunt man but graduated to acting parts because of his suitably Russian looks and had been engaged to play Blofeld's chief heavy, Gunther, in OHMSS. George Leech, still active and one of the very best fight arrangers in the business, recalls the test as done by Lazenby.

"Before he had done a couple of scenes in tests and then they said, 'Well, we want to see if he's any good at action' - so I had to arrange a fight scene. I had a set built by the art department and I arranged a fight scene there with Yuri Borienko. In fact, I think that was a better fight - the test - than the one we did in the film, although the one in the film was very good."

Leech, like all the stuntmen on the film, was impressed by Lazenby's fitness. "He was a typical Aussie beach type. He'd always been swimming and doing plenty of exercise, so he was a very fit man."

Lazenby confirms this. "I was very physical. I was born that way and I impressed them with my ability to be able to swim, to jump and fight and carry on like a maniac."

Lazenby and Borienko's inexperience in screen fighting led to some injuries during the fight, including a broken nose for Yuri, as Leech recalls.

"Where you're supposed to miss in the right direction, you've still got to be very accurate with your punches even though you don't actually hit your opponent. So much depends also on the reaction of the opponent to make it exactly real. It's got to look like a very good punch and you've got to be very accurate. You've got to keep rehearsing over and over. It does happen occasionally that you get hit."

It was reputedly this fight sequence that was the final factor that convinced the production team that they had found their new James Bond. Peter Hunt in particular was pleased with the choice, having been very impressed with him from the start, as Lazenby acknowledges.

"Four months they tested me before they said, 'Yay.' Peter Hunt was very pro me and, in fact, without Peter Hunt I wouldn't have been there. I would have fallen by the wayside."

"Before he had done a couple of scenes in tests and then they said, 'Well, we want to see if he's any good at action' - so I had to arrange a fight scene. I had a set built by the art department and I arranged a fight scene there with Yuri Borienko. In fact, I think that was a better fight - the test - than the one we did in the film, although the one in the film was very good."

Leech, like all the stuntmen on the film, was impressed by Lazenby's fitness. "He was a typical Aussie beach type. He'd always been swimming and doing plenty of exercise, so he was a very fit man."

Lazenby confirms this. "I was very physical. I was born that way and I impressed them with my ability to be able to swim, to jump and fight and carry on like a maniac."

Lazenby and Borienko's inexperience in screen fighting led to some injuries during the fight, including a broken nose for Yuri, as Leech recalls.

"Where you're supposed to miss in the right direction, you've still got to be very accurate with your punches even though you don't actually hit your opponent. So much depends also on the reaction of the opponent to make it exactly real. It's got to look like a very good punch and you've got to be very accurate. You've got to keep rehearsing over and over. It does happen occasionally that you get hit."

It was reputedly this fight sequence that was the final factor that convinced the production team that they had found their new James Bond. Peter Hunt in particular was pleased with the choice, having been very impressed with him from the start, as Lazenby acknowledges.

"Four months they tested me before they said, 'Yay.' Peter Hunt was very pro me and, in fact, without Peter Hunt I wouldn't have been there. I would have fallen by the wayside."

It would be Hunt's first film as first unit director and he would also be breaking in a new Bond, but such a task held no fears for him.

"Remember, I had done a lot of directing work on the others. Obviously it's like anything creative: although it's a group of people it has to be one person who dominates the scene -which is normally the director. And that was the case where I came into it and I was very dominating, I can tell you. I had great admiration for the producers because basically they were fine producers. They generally left you alone apart from decisions that were put on them by distributors or censors or things like that."

As Lazenby asserts, "He'd been the editor on the others so he understood the whole format and already felt that he could direct them better than the other guys. His confidence was very high.

"My opinion is that if Peter could pull off the Bond film with a new Bond then it gave him more recognition. If he did it with Connery it was: 'Hey, he just told Connery to go through the moves he's already been through.' But here he was putting a new actor - and believe you me, I'm not James Bond. I never behaved that way in real life. Believe it or not, I had to act to a certain degree! I didn't have that accent; I had to change my accent."

This obviously entailed some elocution lessons. "I had a couple, but I was a quick learner. We had to learn pretty quick. We had an acting coach on the set who, as good as he was, I didn't take much notice of because I had my own way of doing things."

Once Lazenby had been decided upon, the main problem was to keep the press from finding out before the official press conference was held to introduce Connery's replacement, and so he was asked to disappear until that time.

"They said, 'Get lost, and if the press find you the deal's off because we're going to deal with Life magazine - front page - and all this stuff to announce the new Bond and we have to give the story to them first. '

"I went to Spain and somebody caught up with me down there. I was coming down the stairway of the hotel I was staying at and I heard a press reporter asking for me at the desk. I had rented a car and I just went out the back window and left because I was afraid of losing the job. And I went to the South of France. I got down there and I called up an old girlfriend of mine who was in London. While she was in-flight Harry had called me and asked me to come back to London. So I met her at the airport, said 'Goodbye,' and got back on a plane and got back to London. It was a mess."

It would be Hunt's first film as first unit director and he would also be breaking in a new Bond, but such a task held no fears for him.

"Remember, I had done a lot of directing work on the others. Obviously it's like anything creative: although it's a group of people it has to be one person who dominates the scene -which is normally the director. And that was the case where I came into it and I was very dominating, I can tell you. I had great admiration for the producers because basically they were fine producers. They generally left you alone apart from decisions that were put on them by distributors or censors or things like that."

As Lazenby asserts, "He'd been the editor on the others so he understood the whole format and already felt that he could direct them better than the other guys. His confidence was very high.

"My opinion is that if Peter could pull off the Bond film with a new Bond then it gave him more recognition. If he did it with Connery it was: 'Hey, he just told Connery to go through the moves he's already been through.' But here he was putting a new actor - and believe you me, I'm not James Bond. I never behaved that way in real life. Believe it or not, I had to act to a certain degree! I didn't have that accent; I had to change my accent."

This obviously entailed some elocution lessons. "I had a couple, but I was a quick learner. We had to learn pretty quick. We had an acting coach on the set who, as good as he was, I didn't take much notice of because I had my own way of doing things."

Once Lazenby had been decided upon, the main problem was to keep the press from finding out before the official press conference was held to introduce Connery's replacement, and so he was asked to disappear until that time.

"They said, 'Get lost, and if the press find you the deal's off because we're going to deal with Life magazine - front page - and all this stuff to announce the new Bond and we have to give the story to them first. '

"I went to Spain and somebody caught up with me down there. I was coming down the stairway of the hotel I was staying at and I heard a press reporter asking for me at the desk. I had rented a car and I just went out the back window and left because I was afraid of losing the job. And I went to the South of France. I got down there and I called up an old girlfriend of mine who was in London. While she was in-flight Harry had called me and asked me to come back to London. So I met her at the airport, said 'Goodbye,' and got back on a plane and got back to London. It was a mess."

The press conference was a bit daunting for young George, especially when Harry Saltzman gave him a warning which amounted to his only preparation for the imminent appearance.

"The only thing was Harry Saltzman said to me before the press conference, 'You know, these guys in here are all sharks. You're in a pool here and they're going to try and eat you for breakfast if they can. So no matter what they say to you, don't let it affect you because they make things up just to get you going, you know.' And that's the only thing. And I said, 'like what?' And I forget exactly what he said, but something to do with my manhood. He said, 'They'll attack that, What are you going to say?' and I said something to Harry like, 'Well, bend over and I'll show you what sort of man I am,' or whatever. And Harry said 'Jesus, don't say that!"'

For the part of Tracy, the girl to whom James Bond would be both husband and widower on the same day, the producers favoured a blonde, continental actress in keeping with Ian Fleming's presentation of the character in the original novel. Peter Hunt recalls that Brigitte Bardot's name came up,

"She was one of the choices. Harry was very keen on her playing the part and went to France to meet with her. I met with her on three occasions. We had lunch and we had drinks in the evening. But on the third visit she just calmly announced that she had just signed a deal to do Shalako - with Sean Connery! So Harry and I looked at one another and that was the end of that."

They then approached Catherine Deneuve, 'Another one of Harry's, because Harry was very Francophile. He was very pro-France. I think he had a company there. I didn't actually meet with her, but she was discussed. I'm not sure she wanted to do it actually. Harry tried to contact her and get her but I don't think she was keen on the idea." Lazenby confirms that she turned it down.

When Diana Rigg's name came up, she seemed an ideal actress to consider with her theatrical experience and her previous involvement with The Avengers TV series, which marked her as an almost too logical choice following on as she does from a previous Avengers girl Honor Blackman into the Bond series. Peter Hunt could see the logic in casting her,

"Perfect, perfect. At the time we got Diana Rigg we were still talking about George Lazenby and my point was that if we were going to have somebody like George Lazenby, who was really not an actor and hadn't done that much, I insisted on having a really good actress. I wanted somebody really excellent and, of course, she jumped to mind. Her agent, Dennis Selinger, was around doing other things and when we broached it to him - 'What about Diana Rigg? Would she be interested?' - he jumped at it and said, 'Well, let me talk to her,' and when I got her, when she said she would do it, there was no doubt in my mind that we would have her.

"I said to her, 'Now, come on, I m going to take you to dinner with George. I want you just to be with him and talk with him. We'll make it a perfectly sociable evening, but afterwards you have to tell me the truth, whether you think you can work with him and do the part.' And that's what happened. We had an enchanting evening; a few bottles of wine and a nice dinner. We really all got on very well. When I spoke to her afterwards, on the next day, she said, 'No trouble at all It will be marvellous. I'll help every way I can.' And I said, 'Well, that s wonderful. Thank you darling. And you're absolutely sure?' So she said, 'Yes, I'm sure."'

The rest of the casting went smoothly, with Telly Savalas playing Ernst Stavro Blofeld and distinguished Italian actor Gabriele Ferzetti cast as Tracy's father, Marc Ange Draco, a Union Gorse Capo. The supporting cast of the film ranks as one of the most impressive of any Bond film, with Ferzetti adding real class with his performance and Savalas being arguably the best screen Blofeld. Peter Hunt took a close interest in the whole process.

The press conference was a bit daunting for young George, especially when Harry Saltzman gave him a warning which amounted to his only preparation for the imminent appearance.

"The only thing was Harry Saltzman said to me before the press conference, 'You know, these guys in here are all sharks. You're in a pool here and they're going to try and eat you for breakfast if they can. So no matter what they say to you, don't let it affect you because they make things up just to get you going, you know.' And that's the only thing. And I said, 'like what?' And I forget exactly what he said, but something to do with my manhood. He said, 'They'll attack that, What are you going to say?' and I said something to Harry like, 'Well, bend over and I'll show you what sort of man I am,' or whatever. And Harry said 'Jesus, don't say that!"'

For the part of Tracy, the girl to whom James Bond would be both husband and widower on the same day, the producers favoured a blonde, continental actress in keeping with Ian Fleming's presentation of the character in the original novel. Peter Hunt recalls that Brigitte Bardot's name came up,

"She was one of the choices. Harry was very keen on her playing the part and went to France to meet with her. I met with her on three occasions. We had lunch and we had drinks in the evening. But on the third visit she just calmly announced that she had just signed a deal to do Shalako - with Sean Connery! So Harry and I looked at one another and that was the end of that."

They then approached Catherine Deneuve, 'Another one of Harry's, because Harry was very Francophile. He was very pro-France. I think he had a company there. I didn't actually meet with her, but she was discussed. I'm not sure she wanted to do it actually. Harry tried to contact her and get her but I don't think she was keen on the idea." Lazenby confirms that she turned it down.

When Diana Rigg's name came up, she seemed an ideal actress to consider with her theatrical experience and her previous involvement with The Avengers TV series, which marked her as an almost too logical choice following on as she does from a previous Avengers girl Honor Blackman into the Bond series. Peter Hunt could see the logic in casting her,

"Perfect, perfect. At the time we got Diana Rigg we were still talking about George Lazenby and my point was that if we were going to have somebody like George Lazenby, who was really not an actor and hadn't done that much, I insisted on having a really good actress. I wanted somebody really excellent and, of course, she jumped to mind. Her agent, Dennis Selinger, was around doing other things and when we broached it to him - 'What about Diana Rigg? Would she be interested?' - he jumped at it and said, 'Well, let me talk to her,' and when I got her, when she said she would do it, there was no doubt in my mind that we would have her.

"I said to her, 'Now, come on, I m going to take you to dinner with George. I want you just to be with him and talk with him. We'll make it a perfectly sociable evening, but afterwards you have to tell me the truth, whether you think you can work with him and do the part.' And that's what happened. We had an enchanting evening; a few bottles of wine and a nice dinner. We really all got on very well. When I spoke to her afterwards, on the next day, she said, 'No trouble at all It will be marvellous. I'll help every way I can.' And I said, 'Well, that s wonderful. Thank you darling. And you're absolutely sure?' So she said, 'Yes, I'm sure."'

The rest of the casting went smoothly, with Telly Savalas playing Ernst Stavro Blofeld and distinguished Italian actor Gabriele Ferzetti cast as Tracy's father, Marc Ange Draco, a Union Gorse Capo. The supporting cast of the film ranks as one of the most impressive of any Bond film, with Ferzetti adding real class with his performance and Savalas being arguably the best screen Blofeld. Peter Hunt took a close interest in the whole process.

"I took a lot of care over the casting. A casting director called Dyson Lovell helped me a great deal with that. I had to have twelve girls - Joanna Lumley started there with me -and Angela Scoular. He helped me all the way with those; I said to him, 'I don't want any scrubbers. I don't want any girlfriends of other producers or people that we have to do a favour for who can 't really act. ' I mean, it's unbelievable. But you know what happens - it's very human and somebody's girlfriend: 'Oh, you must give her a job' - you know, all that sort of thing - and she gets shoved into it. I said, 'Please, these girls have to be very important up there, although they don't do very much.' I cast every one of them separately and they were all actresses and he helped me enormously."

Those cast as Blofeld's unwitting 'Angels of Death' included, as well as the aforementioned two, Catherina Von Schell, Julie Ege, Anoushka Hempel and Jenny Manley. For the role of Irma Bunt, Blofeld's assistant, Saltzman suggested Greek actress Irene Papas, but Hunt rejected her as too sympathetic.

"The big problem with casting was Irma Bunt. I went through a lot of people before I eventually found use Steppat, wonderful German actress, She died, aged 70, the next Christmas, unfortunately. It was the last film that she made. She'd made films in Germany before and she'd been a very big actress before the war. A very glamorous woman she was, I liked her. She was wonderful in it and, again, I took a lot of trouble. I saw other people. In fact, I was getting very despondent, and then use Steppat arrived via a German agent who was awfully finally found what he thought was an ideal site good at finding people. And I knew immediately that this is the one. Cubby was not convinced. So he and I went down there. They opened 80 per cent of the film, any film is casting."

The various locations for the filming, which was scheduled to begin in the Autumn, alreadybeen found. The script closely followed Fleming's book and most of the locations were not too problematic to find in both Portugal and Switzerland. The one difficulty had been in finding a suitable site for Blofeld's mountain fortress, Piz Gloria. Syd Cain, who had previously worked on Dr No (Although uncredited in error) and From Russia With Love, was the production designer and had begun looking for suitable locations in the winter of 1967/8. The initial possibility was very different to the final solution, as he recounts.

"Harry Saltzmann said to me that he had finally found what he thought was an ideal site for Blofeld and it was in the Maginot Line. So he and I went down there. They opened it all up for us, which was rather something, and we were the only two, plus a guide, in there. The guide took us all the way around in the Maginot Line, down to the hospital section, the kitchen section, the dinning rooms, and up into the gun turrets. Anyway we were going along on the little train and Harry said to me,'Well, what do you think?'

"I took a lot of care over the casting. A casting director called Dyson Lovell helped me a great deal with that. I had to have twelve girls - Joanna Lumley started there with me -and Angela Scoular. He helped me all the way with those; I said to him, 'I don't want any scrubbers. I don't want any girlfriends of other producers or people that we have to do a favour for who can 't really act. ' I mean, it's unbelievable. But you know what happens - it's very human and somebody's girlfriend: 'Oh, you must give her a job' - you know, all that sort of thing - and she gets shoved into it. I said, 'Please, these girls have to be very important up there, although they don't do very much.' I cast every one of them separately and they were all actresses and he helped me enormously."

Those cast as Blofeld's unwitting 'Angels of Death' included, as well as the aforementioned two, Catherina Von Schell, Julie Ege, Anoushka Hempel and Jenny Manley. For the role of Irma Bunt, Blofeld's assistant, Saltzman suggested Greek actress Irene Papas, but Hunt rejected her as too sympathetic.

"The big problem with casting was Irma Bunt. I went through a lot of people before I eventually found use Steppat, wonderful German actress, She died, aged 70, the next Christmas, unfortunately. It was the last film that she made. She'd made films in Germany before and she'd been a very big actress before the war. A very glamorous woman she was, I liked her. She was wonderful in it and, again, I took a lot of trouble. I saw other people. In fact, I was getting very despondent, and then use Steppat arrived via a German agent who was awfully finally found what he thought was an ideal site good at finding people. And I knew immediately that this is the one. Cubby was not convinced. So he and I went down there. They opened 80 per cent of the film, any film is casting."

The various locations for the filming, which was scheduled to begin in the Autumn, alreadybeen found. The script closely followed Fleming's book and most of the locations were not too problematic to find in both Portugal and Switzerland. The one difficulty had been in finding a suitable site for Blofeld's mountain fortress, Piz Gloria. Syd Cain, who had previously worked on Dr No (Although uncredited in error) and From Russia With Love, was the production designer and had begun looking for suitable locations in the winter of 1967/8. The initial possibility was very different to the final solution, as he recounts.

"Harry Saltzmann said to me that he had finally found what he thought was an ideal site for Blofeld and it was in the Maginot Line. So he and I went down there. They opened it all up for us, which was rather something, and we were the only two, plus a guide, in there. The guide took us all the way around in the Maginot Line, down to the hospital section, the kitchen section, the dinning rooms, and up into the gun turrets. Anyway we were going along on the little train and Harry said to me,'Well, what do you think?'

"I said, 'Well, Harry, quite honestly, I could build all this in the studio.' And he got a bit cross - as was his wont - and we just simply turned round and he said, 'Oh, well.' We flew back to Paris in the car that he was driving and he said, 'Well, you find it yourself ' So then I thought, 'Well, instead of going low, we'll go up high.' I had also been to another place he'd seen but it wasn't satisfactory at all. French troops were billeted in there in the mountains."

The search then moved to Switzerland in the hope that Fleming might have based Piz Gloria on an actual place, but this proved not to be the case. Peter Hunt takes up the story;

"We were looking desperately at various places and they were very touristy or they weren't quite right. And we were in St Moritz at the time, having a drink at the bar and this Swiss production manager we had, Hubert Froelich, was talking to some other guy in German. He came over to me and he said, 'I've just been talking to this chap here and I think we might have something that would be just what you're looking for in Murren.'

"And I said, 'Well, tomorrow we're going to look at these stations and things. Why don't you go to Murren, you know what I want, and have a look and if there's any remote possibility that it's usable give me a call and then we'll come down, but we won't make a special visit' - because it was quite a long way away. And that evening he phoned me and said, 'I think you should come and look. I think we've found what we want.' And sure enough, that was so. In making films you've got to have luck. However clever you can be, you must have luck. You have to have luck in good casting and you must have luck in shooting - all sorts of areas. And that was one great piece of luck because there we were looking for that exact place which was in the book. You would have thought it had been built for the book, but it hadn't."

Syd Cain continues, "Then the problem was getting permission to build."

What had been found was a restaurant that was being built on top of the Schiltorn ('Magic Mountain') in the Bernese Overland. From its peak at 9744 feet (2970 metres) it offers one of the best views of the Alps. To the north can be seen the Swiss Lowlands, the Jura and the Black Forest, which as you look round give way to the Alpine range dominated by the Eiger, Monch, and Jungfrau. The building of the restaurant had started in 1961 with helicopters carrying the building materials up to the peak. Syd Cain recalls the state of the construction when he first saw it.

"It was basically there, the foundations were there. It obviously needed a lot of alteration I wanted to do and I wanted to make the inside revolve. But I had a problem with the Government; they said 'No way.' And then I said. 'Well, if I build a heliport attachment to it' - which I wanted to do anyway - 'If we made it for real, you could use it for mountain rescue.' It was right opposite the Eiger and they liked that idea, so they gave us permission to build. And I had to build it for real, of course."

Syd Cain began his construction work in the Spring of 1968. The design of the building was basically his "so that we brought the mountain round to the viewers and then we elaborated from there on. They were going to make it circular; it wasn't going to move."

The search then moved to Switzerland in the hope that Fleming might have based Piz Gloria on an actual place, but this proved not to be the case. Peter Hunt takes up the story;

"We were looking desperately at various places and they were very touristy or they weren't quite right. And we were in St Moritz at the time, having a drink at the bar and this Swiss production manager we had, Hubert Froelich, was talking to some other guy in German. He came over to me and he said, 'I've just been talking to this chap here and I think we might have something that would be just what you're looking for in Murren.'

"And I said, 'Well, tomorrow we're going to look at these stations and things. Why don't you go to Murren, you know what I want, and have a look and if there's any remote possibility that it's usable give me a call and then we'll come down, but we won't make a special visit' - because it was quite a long way away. And that evening he phoned me and said, 'I think you should come and look. I think we've found what we want.' And sure enough, that was so. In making films you've got to have luck. However clever you can be, you must have luck. You have to have luck in good casting and you must have luck in shooting - all sorts of areas. And that was one great piece of luck because there we were looking for that exact place which was in the book. You would have thought it had been built for the book, but it hadn't."

Syd Cain continues, "Then the problem was getting permission to build."

What had been found was a restaurant that was being built on top of the Schiltorn ('Magic Mountain') in the Bernese Overland. From its peak at 9744 feet (2970 metres) it offers one of the best views of the Alps. To the north can be seen the Swiss Lowlands, the Jura and the Black Forest, which as you look round give way to the Alpine range dominated by the Eiger, Monch, and Jungfrau. The building of the restaurant had started in 1961 with helicopters carrying the building materials up to the peak. Syd Cain recalls the state of the construction when he first saw it.

"It was basically there, the foundations were there. It obviously needed a lot of alteration I wanted to do and I wanted to make the inside revolve. But I had a problem with the Government; they said 'No way.' And then I said. 'Well, if I build a heliport attachment to it' - which I wanted to do anyway - 'If we made it for real, you could use it for mountain rescue.' It was right opposite the Eiger and they liked that idea, so they gave us permission to build. And I had to build it for real, of course."

Syd Cain began his construction work in the Spring of 1968. The design of the building was basically his "so that we brought the mountain round to the viewers and then we elaborated from there on. They were going to make it circular; it wasn't going to move."

The cable car link to the mountain was finished by the end of 1967. The cableway had a total length of 22,858 feet (6970 metres), covering an altitude gap of 6,900 feet (2103 metres), but when Syd Cain first visited the peak it was still unfinished, "Originally, when I landed there, I landed by helicopter virtually on the peak. It was quite fun."

The conditions for those involved in the construction were quite hard at. times.

"I got the Italian engineers who had built the Simplon Tunnel and they were a bit fed up climbing up and down everyday, so they asked me if it would be okay if they lived up there. So we built them accommodation to live up there and they asked permission for one of their sisters to come cook for them. They were excellent. We hauled things up originally by helicopter and then we got the cable car going and got some of the stuff up by cable car."

The cable car link to the mountain was finished by the end of 1967. The cableway had a total length of 22,858 feet (6970 metres), covering an altitude gap of 6,900 feet (2103 metres), but when Syd Cain first visited the peak it was still unfinished, "Originally, when I landed there, I landed by helicopter virtually on the peak. It was quite fun."

The conditions for those involved in the construction were quite hard at. times.

"I got the Italian engineers who had built the Simplon Tunnel and they were a bit fed up climbing up and down everyday, so they asked me if it would be okay if they lived up there. So we built them accommodation to live up there and they asked permission for one of their sisters to come cook for them. They were excellent. We hauled things up originally by helicopter and then we got the cable car going and got some of the stuff up by cable car."

Five hundred tons of concrete had to be carried up to the peak in order to construct the helicopter pad. In addition, the film's director of photography, Michael Reed, reckoned that the generator installed was insufficient to provide the lighting for night shooting. As he recalls, "They had to put a helipad in, so while they were doing that I said to the production manager, 'Look, we're going to need another fifteen hundred kilowatts up here, so that we run totally independent. We can't get generators up here, not mobile generators.'

"He said, 'Well, leave that with me.' And he took a fifteen hundred amp generator complex up to the top of Piz Gloria and the civil engineers blasted the rock out for the helipad and they built this fifteen hundred watt generator underneath the helipad. So it was a marvellous bonus for me with the Brutes (lamps) that we were using out there." Since the construction was to be permanent, both interior and exterior, allowances had to be made for the particular conditions on an exposed mountain peak, as Syd Cain notes. "We had to build for tremendous snow pressures and we had to allow for winds of 120 miles per hour. I thought it all went together really well, nice and cheaply really, considering." The total cost was about $60,000, only a fifth of the cost of Ken Adam's volcanic crater for the previous Bond film You Only Live Twice. The interior was completely designed by Cain, who had to build it with a view to its being an acceptable design for when it was opened to the public once filming had been completed as well as keeping it manageable as a set to shoot in. There was no duplication of the interior at Pinewood. "No, it was all done up there. Only the interior scenes like Blofeld's laboratory and cave and the wheelhouse we did at Pinewood." The wheelhouse, with it's vast cogs and wheels which operate the cable car, was made out of wood and was an impressive and remarkably realistic set, which also had to have cogs that worked. "They all had to fit, of course, and not jam. They all had to work. It was quite a large set, and for the shot looking down we did a matte shot." One problem that appeared was discovered by Michael Reed when lighting the interior of Piz Gloria. "Well, we had a situation up there: there was a four-stop difference between exterior and a working interior. We couldn't have a massive amount of light up there to balance up the exterior to the interior because it would have been unworkable. First of all, you could never have got the lamps big enough that we needed to go into the place."

"Well, we had a situation up there: there was a four-stop difference between exterior and a working interior. We couldn't have a massive amount of light up there to balance up the exterior to the interior because it would have been unworkable. First of all, you could never have got the lamps big enough that we needed to go into the place."

Being a solid set, space was also confined - "and we weren't just shooting standing shots. We were tracking and doing things like that. We had a small crane to start with. And so what I did, I got in touch with ICI to discuss a question of neutral densities and colour correction for blue up there - which was a salmon pink. We wanted to do tests. I went up there and we did tests on different colours of gelatine just for experimental purposes. We chose one and I took it to ICI and I said, 'Look, you're going to do the neutral densities for me - give me three stops. I need acrylic sheeting coloured in this colour to balance up the blue.' So they said yes, they could do it."

Reed meanwhile went to Ireland for three months to shoot a Disney film, Guns in the Heather, and made contact again. "I phoned ICI and they said, 'Well, it's fine Neutral densities are no problem, but we can't meet your shooting date with this 85 filter that you want.' So I then spoke to Syd Cain and I said, 'Is it possible to make up four tanks that we can put the dye in?' - because they had a department at Pinewood at that time for dyeing gelatine. I spoke to Bert Driscoll, who was the head there, and he said, 'Well, if you can get the tanks made up, I'll endeavour to do it for you.' Which he did." "It took about two weeks with him working flat out to dye those acrylic sheets. They were eight feet by six feet and we had to double them up because of the whole dawn sequence of the attack on Piz Gloria. The second-unit cameraman, Johnny Jordan, had shot all this stuff with the helicopters flying with the dawn sky and it was marvellous. What he did was a wonderful job. And so I had to do that to double up on that. "So it was quite a feat. Everyone was so good because they all pulled their weight and they did their utmost to get it done - even top the packaging of it all." The windows at Piz Gloria also had special mouldings for ease of fitment of the sheets. "They were interchangeable and it worked out extremely well actually." Cain also had to organise the construction of a bobsleigh run for the climactic chase and fight between Blofeld and Bond.

"We were going to use the original Cresta Run but we found that it wasn't very practical and it wasn't very exciting, to be quite honest. So we designed another one and had it made by local snow experts. We worked to their specifications really and it all seemed to yell quite well."

Since a basic premise of the plot is Blofeld's snobbery in his desire to be recognised as a Count, which allows Bond to infiltrate his hideout by impersonating Sir Hilary Bray of London's College of Arms as he supposedly researches Blofeld's claim, another task which fell upon Cain was the design of the Blofeld coat of arms, a large scale version of which was mounted in Piz Gloria.

"I designed it and then I went to the College and they put me right. For example the crown: there were nine pearls and I'd just drawn ten and they said, 'Oh, no, no, no. There'll have to be nine to show his rank' - odd things like that which they very kindly corrected for me. I think I had the wrong number of diamonds in, but basically the actual boar motif was a Blofeld character. We found that, we went into that. That was quite interesting. So the whole thing is authentic. I designed it in co-operation with the College of Arms."

Meanwhile, in London, Richard Maibaum had completed his script, which remained very close to the original book, although with some significant additions which included the scene in Gebruder Gumbold's office in Berne where Bond opens a safe and photocopies documents relating to Blofeld's title claim using a computer unit passed to him by crane from a building site opposite. Peter Hunt, like many directors was also involved in the script process.

"I had a big hand in the script, wrote quite a lot of it as we went, although Maibaum quite justifiably gets the credit because he did it all first. There's a lot of things that were added as we went."

Novelist Simon Raven also worked on the script. "He did some good dialogue for me. He made some of the dialogue much more intelligent than it really was. It wasn't quite so cardboardy. By that I don't mean to denigrate Richard Maibaum. Certainly with a big spectacular action film you really are working all the time at it and certain things present themselves when you start rehearsing them and setting them up, both in dialogue and in the way that you do it. A script for that sort of thing is not like doing a play where you've got words that really have to have meaning."

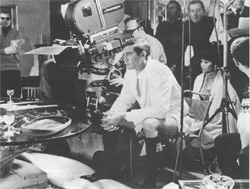

With Piz Gloria ready, shooting began in October 1968, with Peter Hunt determined to avoid faking any shots with studio inserts if it could be avoided.

"We shot it all there irrespective sometimes of the weather, because sometimes it got clouded over. But I was very insistent on not doing anything back projection and all that sort of thing. But we shot it all up there and I think it makes the film much better because of it. And Michael Reed, he was a marvellous cameraman, he really was super; the whole unit were great, very nice people."

One of George Lazenby's first scenes as James Bond was at the dining table where, as Sir Hilary he sits among the girls that Blofeld is curing of their various allergies wearing a kilt. In the scene Irma Bunt stops Ruby Barlett (Angela Scoular) from giving Sir Hilary her room number. Undaunted she puts her hand under his kilt and writes her number on his thigh with her lipstick. The crew decided that this scene had great potential for a practical joke, as George Lazenby recalls.

Cain also had to organise the construction of a bobsleigh run for the climactic chase and fight between Blofeld and Bond.

"We were going to use the original Cresta Run but we found that it wasn't very practical and it wasn't very exciting, to be quite honest. So we designed another one and had it made by local snow experts. We worked to their specifications really and it all seemed to yell quite well."

Since a basic premise of the plot is Blofeld's snobbery in his desire to be recognised as a Count, which allows Bond to infiltrate his hideout by impersonating Sir Hilary Bray of London's College of Arms as he supposedly researches Blofeld's claim, another task which fell upon Cain was the design of the Blofeld coat of arms, a large scale version of which was mounted in Piz Gloria.

"I designed it and then I went to the College and they put me right. For example the crown: there were nine pearls and I'd just drawn ten and they said, 'Oh, no, no, no. There'll have to be nine to show his rank' - odd things like that which they very kindly corrected for me. I think I had the wrong number of diamonds in, but basically the actual boar motif was a Blofeld character. We found that, we went into that. That was quite interesting. So the whole thing is authentic. I designed it in co-operation with the College of Arms."

Meanwhile, in London, Richard Maibaum had completed his script, which remained very close to the original book, although with some significant additions which included the scene in Gebruder Gumbold's office in Berne where Bond opens a safe and photocopies documents relating to Blofeld's title claim using a computer unit passed to him by crane from a building site opposite. Peter Hunt, like many directors was also involved in the script process.

"I had a big hand in the script, wrote quite a lot of it as we went, although Maibaum quite justifiably gets the credit because he did it all first. There's a lot of things that were added as we went."

Novelist Simon Raven also worked on the script. "He did some good dialogue for me. He made some of the dialogue much more intelligent than it really was. It wasn't quite so cardboardy. By that I don't mean to denigrate Richard Maibaum. Certainly with a big spectacular action film you really are working all the time at it and certain things present themselves when you start rehearsing them and setting them up, both in dialogue and in the way that you do it. A script for that sort of thing is not like doing a play where you've got words that really have to have meaning."

With Piz Gloria ready, shooting began in October 1968, with Peter Hunt determined to avoid faking any shots with studio inserts if it could be avoided.

"We shot it all there irrespective sometimes of the weather, because sometimes it got clouded over. But I was very insistent on not doing anything back projection and all that sort of thing. But we shot it all up there and I think it makes the film much better because of it. And Michael Reed, he was a marvellous cameraman, he really was super; the whole unit were great, very nice people."

One of George Lazenby's first scenes as James Bond was at the dining table where, as Sir Hilary he sits among the girls that Blofeld is curing of their various allergies wearing a kilt. In the scene Irma Bunt stops Ruby Barlett (Angela Scoular) from giving Sir Hilary her room number. Undaunted she puts her hand under his kilt and writes her number on his thigh with her lipstick. The crew decided that this scene had great potential for a practical joke, as George Lazenby recalls.

"I didn't play it. The crew played it and used me as the dummy. They strapped a sausage to my leg - a big, warm German sausage about a foot and a half long - and Angela put her hand under there and they all expected a surprised reaction on her face, but she just coolly waited until the scene was over and said to me, 'You're not wearing any pants.' I was a little shy with Angela after that."

There was obviously quite a bit of waiting around as the lighting was set for a scene particularly with the added difficulties up at Piz Gloria. As Michael Reed explains, "Our big problem was, of course, the whole 360 degree interior there was glass and every time we put a lamp up it was reflected in the glass. So we had to flag everything off so that you couldn't see any of the highlights from the lamps itself. Obviously that took time and it was quite something, but even then we still kept fairly to schedule. It wasn't easy by a long way!"

"I didn't play it. The crew played it and used me as the dummy. They strapped a sausage to my leg - a big, warm German sausage about a foot and a half long - and Angela put her hand under there and they all expected a surprised reaction on her face, but she just coolly waited until the scene was over and said to me, 'You're not wearing any pants.' I was a little shy with Angela after that."

There was obviously quite a bit of waiting around as the lighting was set for a scene particularly with the added difficulties up at Piz Gloria. As Michael Reed explains, "Our big problem was, of course, the whole 360 degree interior there was glass and every time we put a lamp up it was reflected in the glass. So we had to flag everything off so that you couldn't see any of the highlights from the lamps itself. Obviously that took time and it was quite something, but even then we still kept fairly to schedule. It wasn't easy by a long way!"

But Lazenby was never at a loose end; "There was a lot of waiting around but I always had things to do. I was working with the second unit doing my own stunts and I was always getting fitted out for something or doing interviews. I never really had a lot of time when I was sitting around. The others did - Telly did, Diana did." Press interest was intense and dealing with journalists was something that he quickly came to dislike. "It was the press that were driving me crazy because I had to do interviews all the time. Being the new Bond, it was just constant interviews."

He also found himself pestered by the local girls, but he was better able to cope with that. "Well, I was pestering them too because, bear in mind, I was a single guy." He was also enjoying the pampered lifestyle of a movie star. "It wasn't too bad for me. I had the run of the place. I could have anything on the menu; I didn't have to eat the film food! I could have the best wines, the best food. I could go to any restaurant. I could do whatever I liked up there and also I had all those girls to entertain me. They were fun. They had their boyfriends coming backwards and forwards, so we all had a great time." The stunt crew on the film have nothing but praise for Lazenby and his co-operative behaviour on what was mainly second-unit work, especially as any kind of physical effort took its toll at such a high altitude. Alf Joint was one of the stuntmen on the film and remembers just how bad it could be. "One of the sparks passed out just trying to change his overalls. The air was so thin, you realised it then. I thought it was a heart attack, but it's just that he'd passed out through lack of oxygen humping all those big Brutes about." Michael Reed adds, "It was pretty tough for them up there because there's quite a difference. Amazing, really." Reed also recalls another unusual phenomenon. "The other thing was the amount of static that was in the actual restaurant area. The hairdressers used to go to George to get his hair right, comb his hair, and you would actually see a flash from the fingers onto George! It was quite something. As a matter of fact he got upset a couple of times because it's such a startling thing." Of Lazenby, Alf recalls "I used to chat quite a lot to him. I don't know what it is, but it was hype: they said he was arrogant. Well, he was always very gentle with kids and he was never rude. Every time I was in contact with George he was as sweet as a nut. I never heard him say a thing wrong. He was always chatting to the girls and helping them out in shots." George Leech's impression of the star was similarly favourable. "He was quite good for what I wanted of him. He did exactly as he was asked to and was quite interested in it. His only problem really was the critics. He had an unfortunate manner of upsetting the newspaper people who went out to interview him. He was a bit cocky. Instead of being more humble and putting on a front of 'I want to learn all I can and hope I can come up to the standard of Sean Connery' and all that sort of stuff. He should have put on the very humble front. Instead of that he was exaggerating the front and upsetting these newspaper people who couldn't wait to crucify him. And when the film came out, although it was a good film the public got the impression that it wasn't a good film because they were out gunning for poor old Lazenby."

Lazenby was unfortunately a little too naive to cope with some of the bitchiness that can be found in a film crew. George Leech continues,

"I think there was one mischievous stuntman; he was a stand-in originally for Roger Moore on The Saint and he finally became a stuntman. He did a bit of whispering in Lazenby's ears I think and probably stirred things up a bit by telling him how a film star should act and all that business. Of course, being inexperienced I suppose he didn't realise he was being set up by somebody whispering in his ear."

Lazenby himself recounts one such incident, which was not calculated to endear him to Peter Hunt.

"It was at the very beginning of the movie, on the first week of shooting. There were some people on the set that were friends of Peter's and the crew said, 'Can't you do something about these guys? They're getting in our bloody way.' And I said, 'Look, can I get these people out of my eyeline here and of off the set?' That's what the crew set me up to say!"

Lazenby has claimed that he was given little help with his performance by Peter Hunt and it remains a controversial issue, although it is difficult to credit that there was a total breakdown of communication between director and budding star, as Peter Hunt verifies.

"You can't direct a film with somebody who's not talking. He may have got a bit angry with me at times, but I didn't mind because sometimes I wanted him to be angry in the scene in order to help him with the performance. But there was no time that we didn't converse. We had to converse."

Michael Reed verifies this. "I mean, they have to, just for directions for what he has to do. He has to be spoken to. It was never gone through a third party or anything like that. Also, it was sad really, because there was a lot of misunderstanding. Some of the things Lazenby did were extremely good. He looked very good in fight sequences. I think that he's a bit lacking experience, but other than that I think he could have gone on because he had some very good double-takes in that, with his reactions very similar to Cary Grant. Peter was the one who gave him everything; he gave him every opportunity."

Exterior filming up at Piz Gloria was particularly difficult because the weather was not exactly as expected, as Hunt confesses. "We had the mildest winter for forty years. We couldn't believe it! But there you are; we overcame that by bringing the snow and putting it around and that sort of thing."

"He was quite good for what I wanted of him. He did exactly as he was asked to and was quite interested in it. His only problem really was the critics. He had an unfortunate manner of upsetting the newspaper people who went out to interview him. He was a bit cocky. Instead of being more humble and putting on a front of 'I want to learn all I can and hope I can come up to the standard of Sean Connery' and all that sort of stuff. He should have put on the very humble front. Instead of that he was exaggerating the front and upsetting these newspaper people who couldn't wait to crucify him. And when the film came out, although it was a good film the public got the impression that it wasn't a good film because they were out gunning for poor old Lazenby."

Lazenby was unfortunately a little too naive to cope with some of the bitchiness that can be found in a film crew. George Leech continues,

"I think there was one mischievous stuntman; he was a stand-in originally for Roger Moore on The Saint and he finally became a stuntman. He did a bit of whispering in Lazenby's ears I think and probably stirred things up a bit by telling him how a film star should act and all that business. Of course, being inexperienced I suppose he didn't realise he was being set up by somebody whispering in his ear."

Lazenby himself recounts one such incident, which was not calculated to endear him to Peter Hunt.

"It was at the very beginning of the movie, on the first week of shooting. There were some people on the set that were friends of Peter's and the crew said, 'Can't you do something about these guys? They're getting in our bloody way.' And I said, 'Look, can I get these people out of my eyeline here and of off the set?' That's what the crew set me up to say!"

Lazenby has claimed that he was given little help with his performance by Peter Hunt and it remains a controversial issue, although it is difficult to credit that there was a total breakdown of communication between director and budding star, as Peter Hunt verifies.

"You can't direct a film with somebody who's not talking. He may have got a bit angry with me at times, but I didn't mind because sometimes I wanted him to be angry in the scene in order to help him with the performance. But there was no time that we didn't converse. We had to converse."

Michael Reed verifies this. "I mean, they have to, just for directions for what he has to do. He has to be spoken to. It was never gone through a third party or anything like that. Also, it was sad really, because there was a lot of misunderstanding. Some of the things Lazenby did were extremely good. He looked very good in fight sequences. I think that he's a bit lacking experience, but other than that I think he could have gone on because he had some very good double-takes in that, with his reactions very similar to Cary Grant. Peter was the one who gave him everything; he gave him every opportunity."

Exterior filming up at Piz Gloria was particularly difficult because the weather was not exactly as expected, as Hunt confesses. "We had the mildest winter for forty years. We couldn't believe it! But there you are; we overcame that by bringing the snow and putting it around and that sort of thing."

As stunt arranger, one of George Leech's toughest tasks was to work on the scenes involving Bond hanging onto the cables outside Piz Gloria after he has escaped from the wheelhouse.

"I had some cables which went through my arms on a harness so that I could actually hook on, so that you could hang on there for quite a long time. Then I tried it out. I had a second unit camera crew that did some tests with myself hanging on the cable and moving along there with the cable car approaching. They were sent back to England and they said, 'Yes, okay. That's what we want.' "And then when it came to it, one day I was on the cable doing exactly that - shooting the test scene - and the cable car suddenly stopped. Everything stopped. Because the first unit was shooting just inside Piz Gloria with the principals and they just called out, 'Silence! Quiet!' and everything stopped. And I'm left there hanging on the wire and no-one's telling me what's happening. I was furious." However, even worse was to come for him at a later date. For his scenes on the cable, Leech wanted to ensure that he was in top physical condition. "The cables went right inside the building itself They were the thickness of a piece of metal scaffolding and I used to practise on that all day when there was a break, swinging on it and climbing hand over hand and doing pull ups. So I thought to myself, 'Well, I've rot all the strength to do this,' but I never reckoned that I would slip and dislocate the arm. That finished my tricks on the cable.

"Although I was there to double as well, I had another three or four other fellas that we could use as doubles, and, when it came to it, my hand slipped because the cable was greasy. I grabbed hold of it and having missed with one hand, still hanging on, you twist around. That's it. You can't stop yourself twisting and the shoulder just goes 'crunch' and off I came. But one of our jobs is to try to get things safe o that you don't have accidents. So I prepared a bed underneath of boxes and mattresses in case myself or anyone else fell off. And, of course, I hurtled down and 'splosh!' - that was it.

"I knew my shoulder was gone and called immediately for somebody else and he couldn't get into the costume. He said, 'Oh, I've put on a bid of weight.' So I called the other one - Chris Webb - and he went up there, by which time we got another shot of him. Myself and Dickie Graydon went up to the top and hooked him on with these cables and hooks and shot some stuff with him.

"Later we shot some stuff in the studio with George Lazenby climbing along the cable. He was quite strong enough to do all that. Of course, you couldn't risk him on the real thing high on the cables, but in the studio you could do it with him."

Lazenby also did the sequence in the wheel house set where he eases himself along the cable.

"Even though he was in the studio on the cable there, I had a bed prepared underneath all the way along the cable just in case he fell off. Well, he did fall off once and enjoyed it, so he did it again!"

Within this sequence is one of the most satisfying moments in any Bond film as regards showing the character as a resourceful man of action. When Bond decides to attempt to climb along the cable in the wheelhouse, he realises he cannot do it with his bare hands - so tears the pockets out of his trousers to use as a pair of makeshift gloves. This bit of business was not in the shooting script, as Peter Hunt explains,

on it and climbing hand over hand and doing pull ups. So I thought to myself, 'Well, I've rot all the strength to do this,' but I never reckoned that I would slip and dislocate the arm. That finished my tricks on the cable.

"Although I was there to double as well, I had another three or four other fellas that we could use as doubles, and, when it came to it, my hand slipped because the cable was greasy. I grabbed hold of it and having missed with one hand, still hanging on, you twist around. That's it. You can't stop yourself twisting and the shoulder just goes 'crunch' and off I came. But one of our jobs is to try to get things safe o that you don't have accidents. So I prepared a bed underneath of boxes and mattresses in case myself or anyone else fell off. And, of course, I hurtled down and 'splosh!' - that was it.

"I knew my shoulder was gone and called immediately for somebody else and he couldn't get into the costume. He said, 'Oh, I've put on a bid of weight.' So I called the other one - Chris Webb - and he went up there, by which time we got another shot of him. Myself and Dickie Graydon went up to the top and hooked him on with these cables and hooks and shot some stuff with him.

"Later we shot some stuff in the studio with George Lazenby climbing along the cable. He was quite strong enough to do all that. Of course, you couldn't risk him on the real thing high on the cables, but in the studio you could do it with him."

Lazenby also did the sequence in the wheel house set where he eases himself along the cable.

"Even though he was in the studio on the cable there, I had a bed prepared underneath all the way along the cable just in case he fell off. Well, he did fall off once and enjoyed it, so he did it again!"

Within this sequence is one of the most satisfying moments in any Bond film as regards showing the character as a resourceful man of action. When Bond decides to attempt to climb along the cable in the wheelhouse, he realises he cannot do it with his bare hands - so tears the pockets out of his trousers to use as a pair of makeshift gloves. This bit of business was not in the shooting script, as Peter Hunt explains,

"I said,'"My God, how does he clasp that cable, because it's all greasy? Could he have gloves with him or something?' - which would have seemed very contrived! And then suddenly I thought, 'Ah! I know what to do!' That's why you've got to have luck."

Peter Hunt's insistence on realism meant that Leech had to get his shots for the cable sequence as it stood. "There was no process stuff on that. It was all the actual cable car. I tried to trace the test shot that I did on the cable when the cable car was approaching with me hanging on. It was shot in such a way that it was looking over the mountains, so it looked a hell of a lot higher than it was."

The stunt required absolute precision as the huge cable car moved towards a very vulnerable stuntman.

"You've got to make sure that someone is in control - that the thing is coming toward you and is going to stop when you want it to stop! But that was also my trying out of the actual cable going through my arms onto these hooks that I made up. Luckily I did, because that time when they said 'Stop' and I'm just left hanging there, there was no way you could hang on with your bare hands on that thing."

Despite the lessons of Leech on the cable, one of the stunt men was still convinced that it could be done without any kind of additional support.

"He reckoned he could do it free-hand Myself and Chris Webb had done it and then Dickie Graydon said, 'Well, I could do it without the hooks.' And I said, 'Well, if you can, you can have another go and you'll get paid for it - for doing it free-hand ' We were all paid extra money for doing this.

"But when he got there it was just getting dark and a frost had formed and there was no way he could hang on to it at all. So anyway, we put the hooks on him so he could go and then he just started sliding down the damn thing. But it was a good shot anyway: the snow was falling. Luckily, I had men stationed to catch him on the next big metal tower that they hang on these cables.

"He was very courageous, that Dickie Graydon. He was a great 'high' man, always wanted to be climbing up. In fact, when we were out there he tried to climb the Eiger, but he didn't get very far. He used to love hanging precariously from somewhere. As long as they use their heads. I think he did some in You Only Live Twice in the volcano - Bond climbing up with suction pads. And, of course, that was Dickie Graydon upside down doing his clinging on the wall bit. A fly on the wall. He loved all that. We always said he was frustrated cat burglar!"

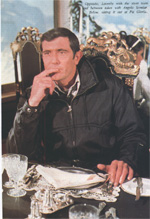

Back with the first unit, things were going reasonably smoothly. With all the waiting around, Telly Savalas was indulging his obsessive passion for gambling, which usually meant he was losing his money as quickly as he was earning it. Always on the lookout for a gambling partner, he even got George Lazenby in on it on one occasion.

"He tried to take my per deum off me at one stage there gambling and Harry Saltzman moved in and took my place - and got the money back! He said, 'Now leave my boy alone!' He gave me protection."

Peter Hunt remembers Savalas with affection and could see that the actor was relishing his meaty role.

"I said,'"My God, how does he clasp that cable, because it's all greasy? Could he have gloves with him or something?' - which would have seemed very contrived! And then suddenly I thought, 'Ah! I know what to do!' That's why you've got to have luck."

Peter Hunt's insistence on realism meant that Leech had to get his shots for the cable sequence as it stood. "There was no process stuff on that. It was all the actual cable car. I tried to trace the test shot that I did on the cable when the cable car was approaching with me hanging on. It was shot in such a way that it was looking over the mountains, so it looked a hell of a lot higher than it was."

The stunt required absolute precision as the huge cable car moved towards a very vulnerable stuntman.

"You've got to make sure that someone is in control - that the thing is coming toward you and is going to stop when you want it to stop! But that was also my trying out of the actual cable going through my arms onto these hooks that I made up. Luckily I did, because that time when they said 'Stop' and I'm just left hanging there, there was no way you could hang on with your bare hands on that thing."

Despite the lessons of Leech on the cable, one of the stunt men was still convinced that it could be done without any kind of additional support.

"He reckoned he could do it free-hand Myself and Chris Webb had done it and then Dickie Graydon said, 'Well, I could do it without the hooks.' And I said, 'Well, if you can, you can have another go and you'll get paid for it - for doing it free-hand ' We were all paid extra money for doing this.

"But when he got there it was just getting dark and a frost had formed and there was no way he could hang on to it at all. So anyway, we put the hooks on him so he could go and then he just started sliding down the damn thing. But it was a good shot anyway: the snow was falling. Luckily, I had men stationed to catch him on the next big metal tower that they hang on these cables.

"He was very courageous, that Dickie Graydon. He was a great 'high' man, always wanted to be climbing up. In fact, when we were out there he tried to climb the Eiger, but he didn't get very far. He used to love hanging precariously from somewhere. As long as they use their heads. I think he did some in You Only Live Twice in the volcano - Bond climbing up with suction pads. And, of course, that was Dickie Graydon upside down doing his clinging on the wall bit. A fly on the wall. He loved all that. We always said he was frustrated cat burglar!"

Back with the first unit, things were going reasonably smoothly. With all the waiting around, Telly Savalas was indulging his obsessive passion for gambling, which usually meant he was losing his money as quickly as he was earning it. Always on the lookout for a gambling partner, he even got George Lazenby in on it on one occasion.

"He tried to take my per deum off me at one stage there gambling and Harry Saltzman moved in and took my place - and got the money back! He said, 'Now leave my boy alone!' He gave me protection."

Peter Hunt remembers Savalas with affection and could see that the actor was relishing his meaty role.

"He loved it, he loved it. He loved me. I used to have to give him a cuddle every day. He was quite sweet. I think he was the best Blofeld that we had."

Gabriele Ferzetti and Diana Rigg were also on location when Lazenby's confidence was beginning to grate on some of the more experienced cast members. Despite his inexperience, George was always keen to put forward suggestions for the benefit of the film, but they did not always meet with much enthusiasm, as he recalls.

"They listened but most of the time they didn't take any notice! I had my finger in the pie but most of the time it was Peter's deal."

George Leech corroborates this.

"I understand that he was a bit flash with the other actors. He was working with such experienced actors - Diana Rigg, Gabriele Ferzetti, George Baker - and he finishes up telling them what to do. Fatal, isn't it? Although they'll be well mannered, it gets up their noses when he starts suggesting little bits of business with their hands when they're sitting at the table and whatnot.

"He was just full of beans. He was a young guy full of the joys of life and, unfortunately, he should have been a bit more humble."

By a curious set of circumstances, Lazenby had begun shooting the film without having actually signed a proper contract.

"What happened was they got me to sign a letter of intent to say that I'd do five movies over seven years or something like that. They couldn't sign me to a contract because I didn't have a lawyer and I didn't have anyone read it. The contract was like a shoe-box! So I gave it to a guy I knew because I didn't have a lawyer and he was a real estate lawyer. So he started reading it and he hadn't understood it until the end of the picture."

George Leech confirms that the crew were aware of the trouble brewing between Lazenby and the producers. "I did hear that he had upset the producers by not signing his contract, even though once they'd started shooting it was a bit dizzy of the producers really not to have him signed up from the word go."

Lazenby's enthusiasm for being the new James Bond was also being subtly eroded due to the influence of one of his supposed friends who was very much keyed into the changing times of the late sixties.

"That was a guy called Ronan O'Reilly. He used to run Radio Caroline. He convinced me that Bonds were over - finished. The Hippie Generation was in and it was going to be that conservativeness was out. Films like Easy Rider and all those that were coming out were going to take over.

"He loved it, he loved it. He loved me. I used to have to give him a cuddle every day. He was quite sweet. I think he was the best Blofeld that we had."